Logistics today is an activity that, while selling mobility, mainly manages immobility. Packages stocked in warehouses. Disruptive, emerging models, based on the principles of the Physical Internet, will be much more dynamic.

Read this article in Chinese | Français

ParisTech Review – How would you define the Physical Internet?

Eric Ballot – In simple words, the Physical Internet is applying the principles of the Internet to logistics. A global, open, interconnected network, using a set of collaborative protocols and standardized smart interfaces, in order to send and receive physical goods contained in standard modules – instead of packets of information, as does the Internet.

The container revolution, which disrupted international trade in the last few decades, offered us a first glimpse, with the emergence of a global standard shared by all players and that allowed high consolidation: container lines are now shared by many customers. But the maritime is only one segment of supply chains. Inter-modality remains very limited: in Europe, for example, the efficiency of maritime containers is significantly lower than that of semitrailers. Lastly, the dimensions of a virtually universal tool such as the pallet are not adapted to containers. In short, this is a first step, but there is still a long way to go.

The next steps are more complicated and are being set as we speak. For a better understanding of these issues, the simplest is perhaps to expose the problems that make evolution necessary. These problems can be described in terms of economic efficiency or as environmental issues. But they boil down to this: trucks that travel on our highways, delivery trucks that circulate in our cities, are on average half empty, if not completely empty. Even if it is unrealistic to run at 100% capacity at all times, significant progress can be made. And this progress will provide margins to all players in the chain by decreasing the environmental impact and energy consumption.

Let’s face reality: we ship a lot of containers and packages filled with air. Empty and/or unnecessary trips are far too many, storage systems are often underutilized because they are scaled for the peak. Scattered in a multitude of competing systems, the logistics industry suffers from a huge deficit of efficiency. This type of organization has tangible effects on prices, urban congestion, traffic, pollution…

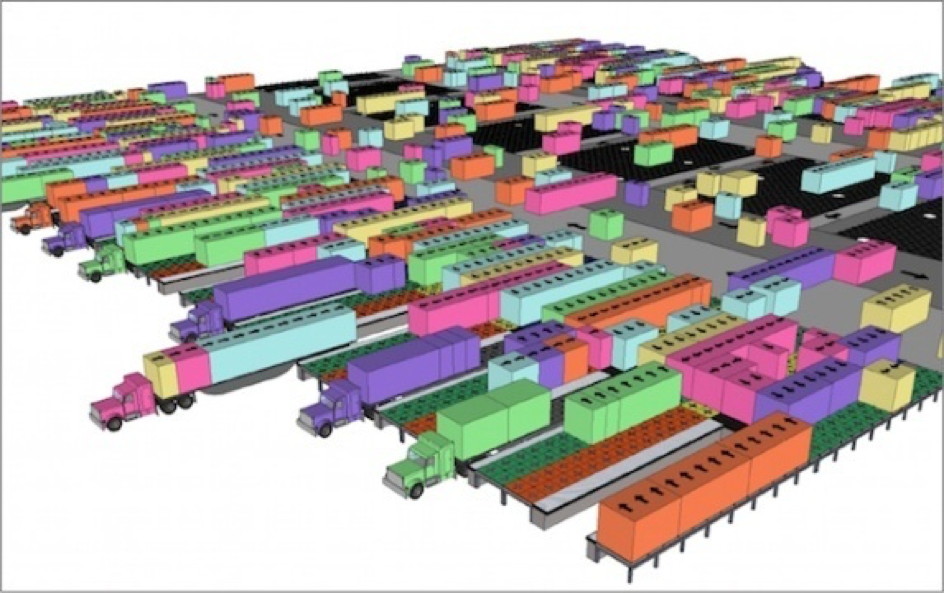

The Physical Internet offers a response to all these challenges by offering large-scale optimization, made possible by streamlining the system, standardizing tools (both hardware and software) and pooling of resources. The basic building block of this system, the equivalent of the package of information flowing through the Internet pipes, is the smart, standardized container. These are currently being developed and we still need to imagine the networks that will deliver them.

You mention an environmental issue. Is the advent of the Physical Internet a logical industrial development, or does it pursue an activist goal?

One can assume that this development will happen “naturally” without any political or regulatory interference. It is even very likely. But there is an even greater risk: that this rise would stem from a logic of “winner takes it all” and lead to a form of monopoly or oligopoly. If we think that we need a greater diversity of solutions, we need to work differently. I don’t know if the term “activist” reflects this idea, but the general idea is to actively promote and spread the concept.

Major players of the field of logistics and distribution such as Amazon, DHL or Alibaba practice a form of activism on these issues: they include services, buy others, and following a logic of platforms. They can also open to other distributors by allowing them, for example, to use their logistics services without selling on their website, or the opposite. Their approach is very clever and leads to streamlining, standardizing and pooling resources. But also and primarily, it calls for reinforcing the networking effect of the central platform, what we call in IT, a “proprietary” system i.e. a system in which only one player has administrator rights.

In this situation, to avoid an oligopolistic concentration between a few competing systems, the only solution is to instill new concepts and rely on relays or groupings that are able to develop their own large-scale solutions. In Europe, for example, hundreds of actors, both industrial and logistics specialists, have joined forces to work on this issue. On a global scale, GS1 already offers a universal communications protocol for logistics events. The Consumer Goods Forum, which brings together manufacturers and distributors, has set up a special task force to tackle the problem of modular containers. Today, the challenge is to mobilize organizations with access to large clients. They are the only actors capable of defining and implementing these protocols.

ISO standardization will be considered only in a second phase, based on the work of these multi-stakeholder platforms. But it must be preceded by an investigative work which will allow for the emergence of experience and practice at the highest standards and their subsequent dissemination.

Specifically, what are the possibilities today?

Several aspects are currently being investigated. We will talk of the software aspects later on, but in terms of physical goods, we need to start with the practical aspects: handling and transportation.

We lack accurate data, but some trends are starting to appear: for example, the atomization of shipments. Everything is tending towards the parcel format and within the next ten years, pallets – a fundamental tool today – and their associated equipment, might well disappear completely.

If the problem translates at the scale of parcels or rather, of smart standardized containers, we need to reflect on several factors: form, capacity, functions and resistance. Should we imagine two, three or more different modular sizes? We also need to reflect on ergonomics: the supply chain is long and on certain segments, handling will be automated. On others, human work remains crucial. How can a box be handled as easily by a robot (without risk of error) than by a human (without risk of lumbago)?

The question of geographic disparities also arises: some countries or sites (especially ports) will be highly automated, others very little. Finally, the perfect container must be indifferent to its vehicle: it can be loaded into shipping containers – trucks – but also scooters, and even bicycles.

As you can see, designing a universal standard requires a significant amount of work. And feedback is crucial. The question of wear on containers, and thus of their reliability, can only be resolved through practice.

In addition, we talk about packages but this minimal unit must be aggregated: we need to think about systems of assembly/disassembly that both play on the solid (a stack of tightly assembled containers) and the fluid (this group is intended to disintegrate, sooner or later, and the main flow will be divided into sub-flows). There is also a need for transport containers of a few cubic meters in connection to existing standards (especially the shipping containers we mentioned earlier).

In addition to these practical aspects, you also mentioned software issues.

The question arises in different terms, in two respects, at the very least. First, physical standards are meant to last, whereas the IT aspect will necessarily evolve. Next, IT tools and equipment must be open, so as to achieve genuine interoperability, and closed, as the information they contain are not all meant to be shared with all.

In this regard, the emergence of the EPCIS standard for the interoperability of traceability databases is most interesting : it opens the possibility of an infrastructure for generating normalized data, allowing everyone to access and process it as they see fit. As a key point, it is “technology independent” from capture modes. In the field of logistics, quality always depends on finer traceability, with sensors able to record multiple data throughout the whole journey: temperature, possible shocks, and of course, geolocation. Traceability is required in order to open networks.

The development of these features, including in real-time, is consistent with the Physical Internet, because it allows for a much finer flow management, with consolidation algorithms and geographic information systems that facilitate adjustments from each operator. Thus, all players can coordinate.

This is the crux of the matter: the key issue of the Physical Internet is to optimize flows. But even on the scale of a single distribution system, of a single carrier, it is still very difficult to anticipate, to set in advance the volume and delivery slots, for example. Some segments, especially in the receiving end, the so-called “last mile,” are particularly sensitive. And current developments, such as delivery in one hour, as promised by Amazon, further complicate the situation. As such, the solution will probably involve the development of new intermediation platforms, not only to locate a truck with capacity –this is already possible – but to organize the concentration of traffic on hubs or networks with transshipments. This business model is already possible for the Physical Internet.

Following this logic of fluidisation of information and coordination of actors would also imply integrating consumers, who could deal for example with one unique contact for all the packages they receive. A sort of provider.

The benefits of an interconnected and open system are very clear. But at the same time, the interest of industry players is not necessarily to share all of their information …

No, indeed: far from it! But this opening logic is not incompatible with a differentiated distribution of rights. The only important issue here is that of cyber-security and therefore, of providing adequate protection for all players involved.

Picking up on your observation and judging by what I see among industrialists, the benefits seem to outweigh the disadvantages. There is a real desire to move forward.

Obviously, there are brakes to the development of the logistics of the future. These include past investments and the cost of legacy, but also the competitive edges of the different actors involved: a major distributor using in a relatively optimal way its own logistics system has less interest than average distributors to develop it. Scale effects play a significant role.

But it also seems that, in the future, network economies offer more attractive prospects than economies of scale. Service requirements are heading in this direction: even for Amazon, which benefits from a strong lever effect, delivering in one hour implies running almost empty trucks while the delivered products are widely available during the same time. The solutions of the Physical Internet, especially in the field of pooling, offer better opportunities for all players, both large and small. The challenge is to create “routers” i.e. logistical centers designed to move packages, but also to store them temporarily, to reroute them in the right direction, in a distributed and allocated manner.

Another factor will be the increase of transportation costs and especially, of its relative cost to handling. The development of the Physical Internet implies adding, on average, one break of load per trip, in the game of bundling/unbundling. Today, this represents a significant cost, which tends to impede the development of the new model. But we are already seeing a relative change in the handling cost compared to the cost of transportation and with automation, this trend is set to continue. Load breaks will be less costly, more fluid, more secure, thanks to standardization, traceability and automation: these are inevitable changes, which have already begun. They will pave the way for the sharing, via transshipment platforms that will integrate each container in optimally managed flows.

Today, logistics is an activity that wishes to work on a just-in-time basis and which, in practice, mainly manages immobility. Packages stocked in warehouses. Logistics modeled on the paradigm of the Physical Internet would be much more dynamic. We would work with flows instead of blocks. This represents considerable productivity gains. Industrials of this sector, as well as the major contractors that support them, are very sensitive to these issues.

The prospects you have opened up are perfectly logical. But nevertheless, we get back to the weight of inheritance, both of today’s tools and proprietary systems. Do you believe in a Big Bang?

No. At least, not in the sense that all this would develop abruptly and painfully. Such a development seems unlikely. However, I observed several phenomena that allow us to envision rapid advances. First of all, key players in the current system – i.e. the world’s leading manufacturer of pallets, or the company that created the barcode – are very interested by the development of this field. They have no intention of watching the train pass and they understood that the transformation has begun.

Second phenomenon: the subject is being raised in seminars and professional conferences. In Asia, a region where needs are growing rapidly but also, where investments in land logistics have been relatively scarce and will likely be hindered by the existing infrastructure – a bit like Africa where mobile phones were adopted directly.

Third phenomenon, the rise of experiments. After all, we are envisioning a global revolution, but more limited initiatives are also possible. This is precisely what we see, especially with the development of pooling, between major customers or distributors, whether around distributors such as Amazon or by the establishment of local platforms such as CRC in France. Eight years ago, when the idea of the Physical Internet was born, we were three around a table. Today, initiatives such as Mix Move Match in Germany claim the concept, without even putting us in the loop. When a concept begins to escape from its creators, the game is well on track.