China and the European Union are two of the biggest traders in the world, trading on average over €1 billion a day. China in 2016 was the largest EU import partner accounting for 20% of EU imports and the EU second largest export partner accounting for 10% of EU export. China’s Belt and Road Initiative launched in 2013, which is to improve the connectivity between Asia, Europe, and Africa by reducing logistics costs, opens new opportunities to Chinese firms in terms of trade and investment. It is the case in Northern Europe in the Baltic Sea Region which is well connected to China by both wings of the Belt and Road: the Maritime Silk Road and the Silk Road Economic Belt.

Read this article in Chinese

The Baltic Sea Region

The Baltic Sea Region (BSR), a European region of some 120 million inhabitants, refers to the 9 states and regions directly bordering the Baltic Sea: Denmark, Sweden, Northern Germany, Northern Poland, the Baltic States, Finland and the region of St. Petersburg in the Federation of Russia. From an economic point of view, it also includes Norway, and Belarus, which share common interests in the development of the Baltic Sea (Map 1).

Map 1 The Baltic Sea Region

Source: Source: Interreg Baltic Sea Region (interreg-baltic.eu)

The countries of the BSR are characterized by a diversity of nationalities and cultures, resources and development level, but their common welfare is intimately linked to international trade and economic cooperation. The Hanseatic League dominated trade for some 400 years in the 15th to 19th centuries in Northern Europe. It was led by German towns and merchants and was based on a powerful network operating along the trade routes of the Baltic Sea and the North Sea.

The Baltic Sea Region today is of strategic importance for both the European Union (EU) and the Federation of Russia. St. Petersburg is Russia’s second largest city with some five million inhabitants in 2016 and the Baltic Sea’s largest port. St. Petersburg is Russian gateway to Scandinavian countries and Western Europe, and has China among its leading trade partners.

The Baltic States (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), after regaining their independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, followed a rapid process of integration with the European Union, but have kept strong trade links with both Belarus, Russia and Central Asia.

Belarus, a landlocked country of 9,5 million inhabitants, has maintained very close political links with Russia since its independence in 1991. It has common borders with Russia, Ukraine and Poland, as well as with Lithuania and Latvia to the North West offering good connectivity with the Baltic Sea.

Norway has no direct shorelines with the Baltic Sea, but has a very close economic relationship with the other Nordic countries and the EU. The EU is Norway’s first foreign trade partner and Norway get the full benefit of freedom of move of persons, goods, services, and capital through the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement.

The EU regional policy for the Baltic Sea Region. The European Union (EU) develops a specific “EU strategy for the BSR macro-region” promoting the economic, social and territorial integration of the region and supporting financially regional projects. The three objectives of the EU strategy in the region are: saving the sea, connecting the region, and increasing prosperity. The EU strategy focuses on the economic and social interests of the EU 8 countries of the BSR representing 85 million inhabitants and 17 percent of EU population, in cooperation with their non-EU neighbors: Russia, Belarus, and Norway.

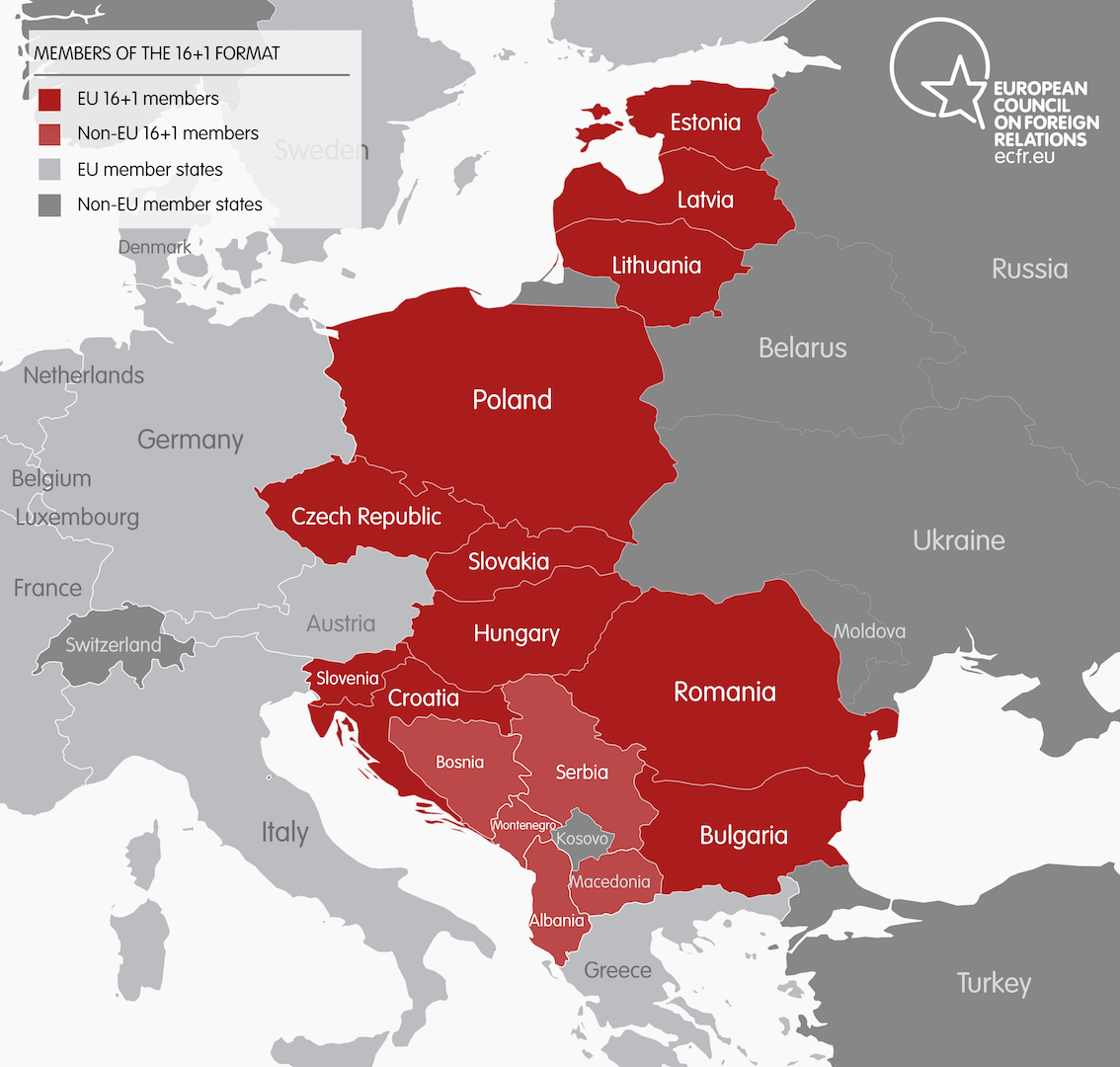

China’s 16+1 framework. China since 2012 is promoting the economic cooperation between China and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries ranging from North to South: from the Baltic Sea to Bulgaria and Romania along the Black Sea, and from Slovenia to Albania along the Adriatic Sea (Map 2).

Map 2: China- Central and Eastern Europe Countries – the 16+1 framework

Source: European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

Poland and the Baltic States, among BSR countries, participate actively in this 16+1 framework, and have a privileged position at the crossroad between two major international communication axis in Europe: the East-West axis from Russia to Germany through Poland and Belarus, and the North-South axis from Northern Europe to the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea.

The Chinese flagship project along this North-South axis is the 350-km high-speed railway project between Belgrade, Serbia and Budapest, Hungary. China Railways and China Communications Construction Co have a key role in the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed rail project on the Chinese side, supported financially by a loan of China EximBank. The project still needs approval from the EU Commission in terms of compliance with EU rules regarding public tenders for large transport projects.

Chinese projects are of course welcome by Hungary and Serbia, and open new perspectives in Southern and Central Europe such as the “Three Seas” initiative, connecting the Baltic, the Black and the Adriatic Sea, currently put forward by the Croatian government in the 16+1 framework.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and the Baltic Sea Region

Germany. Germany (80.7 million inhabitants) is the largest European economy and China’s most important trading partner, accounting for one-third of China-EU trade. In 2016, China was Germany’s fifth-biggest export market after the US, UK, France, and Netherlands, and Germany was the first import partner of China. Germany, followed by Sweden, and Denmark is Chinese leading trade partner among BSR countries (Table 1).

According to European think-tank Bruegel, China’s BRI could lead to an increase of more than 6 percent of China-Europe trade, and Germany would certainly benefit more than other countries from this increase. In 2016 Germany was the largest recipient of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Europe. This situation gives to Germany the leading role in the economic cooperation with China in Europe and the Baltic State Region, as well along the trade routes connecting Germany to China in the Baltic Sea Region and in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) countries.

According to German think tank Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), Chinese investments in the European Union rose 77 percent to over 35 billion euros in 2016, with Germany accounting for 31 percent. In 2016, among other investments, Midea, a leading producer of home appliance acquired Kuka, the leading German robot manufacturer, Beijing Enterprise, an integrated public utilities company, acquired the waste management company Energy from Waste (EEW), and China National Chemical Corporation (ChemChina), the largest enterprise in China’s chemical industry, the industrial machinery maker KraussMaffei.

Poland. Poland (38 million inhabitants) is the largest economy in Central and Eastern Europe, China’s second trade partner after Germany in the Baltic Sea Region, and China’s largest trade partner in Central and Eastern Europe. Poland has thus a key role in the success of the “16+1” framework; Poland is number one Chinese trade partner in the CEE countries (30% of China-CEE trade) and number 2 recipient of Chinese investments after Hungary. Polish authorities express a deep concern about by the huge current trade deficit between the two countries, but would welcome Chinese investments in the transport infrastructure projects. Not surprisingly, the two cities in Poland that are the most eager to work with China in the Belt and Road framework are Łódź, a major hub on the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), and Gdańsk, a leading Baltic seaport.

Table 1 Trade in goods between China and EU Baltic State Region Countries (2016)

| Import Value to the EU

(billion euros) |

Export Value from the EU

(billion euros) |

|

| Germany | 93.8 | 76.1 |

| Poland | 14 | 1.7 |

| Sweden | 7.1 | 4.9 |

| Denmark | 5.6 | 3.8 |

| Finland | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| Lithuania | .7 | .1 |

| Estonia | .6 | .2 |

| Latvia | .4 | .1 |

| EU28 | 345 | 170 |

Source: Eurostat

Nordic Countries. China is the largest trading partner in Asia of Nordic countries: Denmark (5.6 million inhabitants), Finland (5.4 million inh.), Iceland (300,000 inh.), Norway (5 million inh.) and Sweden (9.5 million inh.), and the trade between China and Nordic countries has been consistently growing since China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001. Scandinavian multinationals have a very strong presence in China in terms of sourcing and Chinese investment in Nordic countries, which was quite low in the past, has been growing rapidly especially in the energy and high-tech sector.

Chinese firms such as China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), the largest offshore oil and gas producer in China, are investing in Finland, Norway, Iceland, and in the Arctic. China Sunshine Kaidi New Energy Group, the largest private company in biomass power generation in China, intends to build a large biodiesel refinery in northern Finland.

Nordic countries in the telecom and IT sector have attracted the attention of Chinese companies such as Huawei which set up its first European office in Sweden in 2000 and had in 2016 11 offices with some 800 staff in the Nordic and Baltic region.

The acquisition of Volvo cars in Sweden by Zhejiang Geely in 2010 has demonstrated that such a deal not only was not harmful to Swedish economy, employment or technology, but on the contrary opened unique opportunities to Volvo cars in China. In 2017 Geely Group invested also in Denmark, agreeing to buy almost a third of Saxo Bank, one of Denmark’s biggest banks, in order to expand its activities in the financial services sector.

The Baltic States. Estonia (1.3 million inh.), Latvia (2 million inh.), and Lithuania (3.2 million inh.) have a relatively limited economic cooperation with China. The main trade partners of the Baltic States are EU countries, especially Germany and Scandinavian countries, and Russia. Germany and Nordic countries are also the main foreign investors, but the Baltic States offer interesting opportunities to China in terms of access to the Baltic Sea through the ports of Klaipeda (Lithuania) and Riga (Latvia), well connected to the other ports of the BSR and with good railways connection to China through Belarus along the continental bridge.

Russia. The economic cooperation between Russia and China is growing in terms of trade, and one can observe a relative convergence between China’s Silk Road Economic Belt logistics projects and Russian Eurasian strategy. But the region of St. Petersburg has not yet attracted major Chinese investments apart from the real estate sector with the “Pearl of the Baltic Sea” project launched in 2005, a residential and commercial zone of 205 hectares. The project is supported by the city governments of Shanghai and St Petersburg. It is managed by a consortium of Chinese firms led by Shanghai Industrial Investment (Holdings) Co Ltd (SIHL), which is controlled by Shanghai Municipal Government and financed by the Export-Import Bank of China (China EximBank).

China-Russia and the Arctic Circle. Largest Chinese investment in Russia is in the energy sector: the Yamal LNG plant in the Arctic Circle. The Yamal project, a liquefied natural gas plant located on the Yamal Peninsula, is expected to cost US$27 billion. It is of great importance for China in terms of energy supply and development of Chinese activities along the Arctic shipping routes. Chinese participation includes 15-year loans of $10.6 billion and $1.5 billion from China EximBank and China Development Bank. The Yamal LNG project is operated by Russian Novatek (50,1%) in partnership with French Total (20%), China’s CNPC (20%) and China’s Silk Road Fund (9,9%). Shipments to China from Yamal should take about 18 days using the Northern Sea route.

Another key project in China-Russia cooperation is the Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway (770 km) project. The project is expected to cost USD22.4 billion and would be partly financed by public-private partnerships (PPP). The agreement signed in 2016 specifies that Russian Railways, Russian investment company Sinara Group, China Railway, and China Railway Rolling Stock Corporation (CRRC) the world’s largest supplier of rail transit equipment, will produce in Russia the equipment for the Moscow-Kazan line.

The Baltic Sea container ports and the Maritime Silk Road

China’s Maritime Silk Road has a major economic importance for the ports of the Baltic Sea: Kiel and Lübeck (Germany), Copenhagen Malmö Port (Denmark), Gdańsk and Gdynia (Poland), Stockholm (Sweden), HaminaKotka and Helsinki (Finland), Aarhus (Denmark), Klaipėda (Lithuania), Riga (Latvia), as well as Saint Petersburg (Russia). These port of the BSR are in competition for China trade with the ports of the North Sea, especially Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp.

The first vessel named by COSCO SHIPPING

Source: courtesy of COSCO SHIPPING

Schleswig-Holstein, the Northern federal state of Germany, has its eastern coast is the Baltic Sea, and its western coast is the North Sea: a strategic location for sea traffic, with the Kiel Canal connecting the North Sea and the Baltic. Lübeck, on the eastern coast, is the largest German port on the Baltic Sea.

The connectivity in this region is a priority of the transport policy of the EU: the North Sea-Baltic Corridor connecting the ports of the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea with ports of the North Sea, situated in Northern Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, including roads, railways and inland waterways. The North Sea-Baltic Corridor consists of railways, roads, and waterways connecting the ports of the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea with ports of the North Sea coast in the west: Hamburg, Bremen, Bremerhaven in Germany, Amsterdam and Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and Antwerp in Belgium.

The key role of the Port of Hamburg. China is by far the most important trade partner of Hamburg, Germany’s largest port and Europe’s third largest, located in the North Sea. Hamburg is linked with Chinese ports by 17 liner services including 13 container liner services. 500 Chinese companies have their European head offices in Hamburg, including COSCO, China’s largest shipping company.

The Port of Gdańsk. Gdańsk, in Poland, has also a good potential for development in the framework of China’s Belt and Road initiative and 16+1 framework of cooperation between China and Central Europe. Gdańsk is the transport hub for 40% of China-Poland trade, and the competitiveness of the port depends on its capacity not only to manage efficiently the flow of containers of the largest container ships, but also to offer the best connection by rail and road to the hinterland: large cities and markets such as Warsaw in Poland, Rotterdam in the Netherlands, Berlin and Hamburg and in Germany. This means huge investments to be done at the port level and in the hinterland.

The Port of Klaipėda. China Merchants Group (CMG) is in discussion since 2016 with the authorities of the Port of Klaipėda In Lithuania working to study the feasibility of the extension of the port and the creation of an outer deep-water port able to accommodate larger vessels. The investments in new port facilities and railways connection to the hinterland could be supported financially by Chinese banks or special funds.

Cosco vessel in Greece

Source: courtesy of COSCO SHIPPING

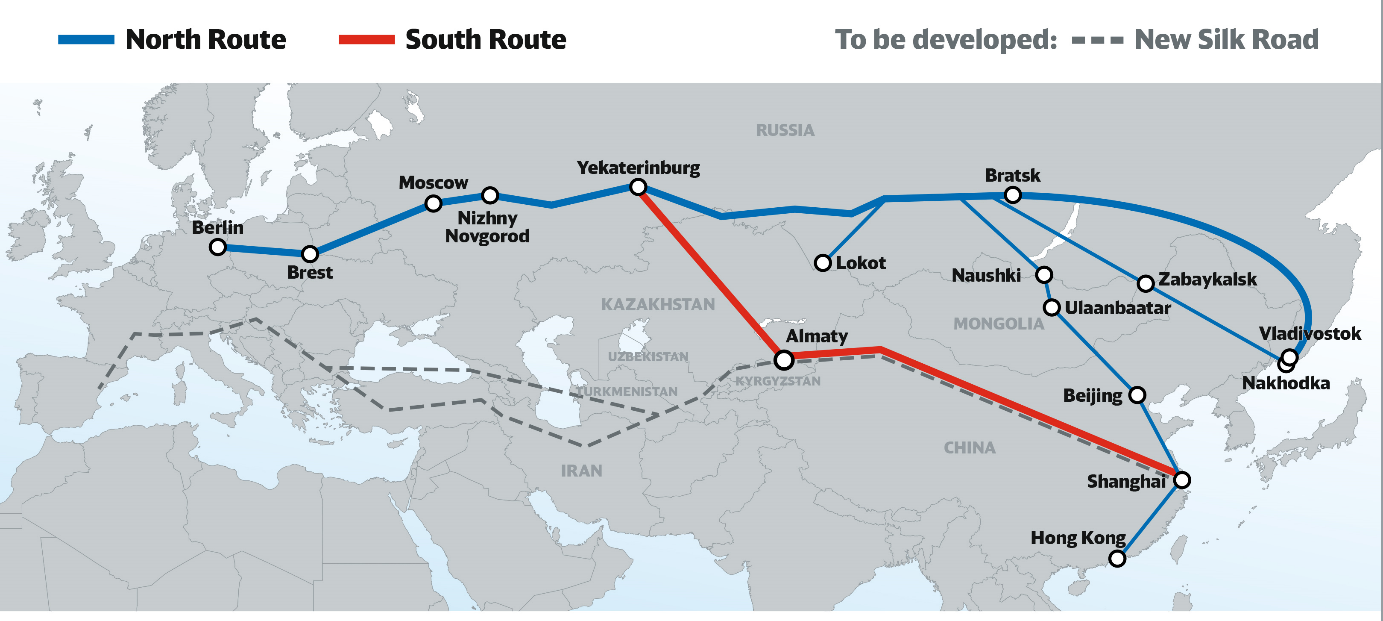

The Baltic Sea Region and China’s Silk Road Economic Belt

From China to Northern Europe through Eurasia, there are two mainland roads: the Northern Route through Siberia crossing Russia from Northern China to Moscow and the Southern Route from Western China to Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, and Central and Central and Eastern Europe. For the Baltic Sea Region, the development of the Southern Route is a great opportunity for trade and economic cooperation with both China and Central Asia. China has already made investments in the transport infrastructure along the way and developed a large logistics hub at the China-Kazakhstan frontier in Khorgos, Korgas Pass which is located 670 Km from Urumqi, the provincial capital of Xinjiang Province, and 200 Km from Astana, the Kazakhstan capital. But going west, other logistics hubs have to be developed.

“Great Stone” – A Chinese land port in Belarus

China is investing since 2015 in a new logistics hub in Minsk, Belarus which offers an ideal location in terms of connectivity. Minsk, the capital city of Belarus, is located 700 Km from Moscow on the North, 1000 Km from Berlin on the South, and 500 Km to the Lithuanian seaport of Klaipeda on the Baltic Sea. On China’s side, the logistics hub and industrial park “Great Stone” is managed by two leading Chinese companies: China National Machinery Industry Corp (Sinomach) and China Merchants Group.

Belarus, Russia, and Kazakhstan belong to the Eurasian Customs Union since 2010, and the products made in Minsk have free access to the Russian market. China’s Midea, in the home appliance business, and Geely car maker are producing in Belarus for the Russian market. The financing of “Great Stone” is supported by Chinese institutions, including the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) which controls the activities of China’s largest State-owned enterprises (SOEs).

The cooperation between Railways Companies along the Belt and Road

Railways companies along the Silk Road Economic Belt cooperate actively to improve the infrastructure and services, manage efficiently the break-of-gauge operations between the Russian and international standard gauge, integrate customs procedures, and eliminate all supply chain barriers. China Railways, Kazakhstan Railways (KTZ), Russian Railways (RZD), Belarus Railways (BC), and their EU counterpart have a common objective: diminishing the number days of transit from China to Europe and making container trains more competitive in China-Europe logistics.

The results are already impressive. The rail cargo service between Chengdu in China and Łódź in Poland began operating in 2013. The Yu’Xin’Ou Rail, connecting China to Germany, stretching 11,000 kilometers from Chongqing to Duisburg, took 14 days in 2016 compared to some 50-55 days by the Maritime Route.

Chinese train reaches now regularly France, Spain and UK.

Deutsche Bahn, the largest railway operator and logistics company in Europe signed an agreement in 2016 with China Railways to develop the cooperation in rail freight transport, high-speed train maintenance, and infrastructure projects in third countries. The two companies expect to triple the number of containers transported by rail along the trans-Eurasian land bridge, by 2020 (Map 3).

Map 3 The Eurasian Land Bridge

Source: Deutsche Bahn, March 2016

Finland, in 2017, is to open a new 8,000-kilometre rail freight route connecting the city of Kouvola in southeastern Finland to Zhengzhou, China, reducing the rail freight transit times from China to 10-12 days, compared to sea transport taking an average of eight weeks.

The National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in 2016 rebranded all freight rail services between China and Europe under the name of “China Railway Express” – “CR Express”. More than a communication exercise, this is clear sign of the commitment of the Chinese government to the Silk Road Economic Belt and the active search for solutions to make more efficient the main routes and some 43 transit hubs connecting China to Europe.

Chinese National Champions and the Belt and Road

Chinese firms entering the BSR are looking for resources such as CNOOC for oil and gas, looking for talents and markets such as Huawei in Sweden and in Finland, and/or looking for technology such as Midea in Germany with Kuka. In the shipping, port management, logistics, construction and railways area, Chinese actors on the Belt and Road are corporate giants such as COSCO, China Merchants, China Railways, and China Railway Construction Corporation Limited. A majority of these companies are State-owned enterprises which have accumulated a very strong experience nationally and internationally. They benefit from China’s government support and the financial support of Chinese banks, financial institutions, China-led development banks such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and Silk Road Fund.

No doubt that in terms of technical capabilities and project management, these companies know how to build a highway, to manage efficiently large port terminals, to develop successfully a high-speed railways network. China’s Belt and Road initiative is a step forward in the Go-Global policy which has already given them the mandate and the opportunity to implement large international projects both in mature economies and emerging markets, through acquisitions or alliances.

COSCO’s strategy in Europe includes these two dimensions: the control of port terminals in European seas: Piraeus in Greece, Kumport in Turkey with China Merchants, Valencia and Bilbao in Spain after the acquisition of a 49 percent of Noatum Port in Spain; alliances and collaborative agreements such the “Ocean Alliance”, created in 2016, a vessel- and slot-sharing agreement, linking French shipping company CMA CGM Group, China Cosco Shipping, Evergreen Line, and Hong Kong-based Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL).

*

Conclusion and Key Issues

General lessons can be learned from Chinese firms’ entry in the Baltic Sea Region. On the Chinese side, there is a full alignment of Chinese government policy, state-owned enterprises strategic moves, and project financing by Chinese-led funds or institutions. There is one vision of national priorities, business interests, and social norms. The same convergence does not exist in most cases among Chinese partners along the Belt and Road, where different forces are pushing in different directions. This could lead to serious misunderstanding and bitter disappointment on both sides with three major issues.

The first issue is the trade imbalance between China and most of its partner countries. Polish regional authorities in Gdansk or Lodz might be strong advocates of Chinese investment in infrastructure, their motivation is not sufficient to convince Polish central government that better transport infrastructure will not increase the trade deficit with China and make it more difficult to Polish companies to resist to Chinese competition. Difficulties can appear at the bilateral, but also bilateral level. Trade deficit is a major preoccupation at the pan-European level, and only Germany and Finland have a reasonably balanced trade with China. The recognition of the “market economy status” of China is subject to a decision of the EU Commission under a qualified majority vote and countries like Greece, Hungary, Spain, and Italy, seeking to attract Belt and Road potential investments, could favor this decision, while other countries could hesitate, and other say no.

The second issue is the social dimension and the participation of the local business community and local workforce to operations linked to Chinese-led investments. The Moscow-Kazan high-speed railway has the blessing of Russia and China top leadership, but the final success of the operation in terms of budget, delay, and quality, depends of the good cooperation between Chinese and Russian companies serving the project in terms of design, components, construction, IT, and services. Thus, Chinese companies have to develop their capabilities of networking, cross-cultural management, and cooperation with local stakeholders, local companies, and local workforce.

The central and western sections of the A1 motorway in Algeria, ranging from the Moroccan to the Tunisian border, have been built in recent years by China Railway Construction Corporation and CITIC. main criticisms against this investment are the relative absence of local companies as subcontractors and the lack of job opportunities for Algerian workers. The interest of Chinese construction companies, which have some 30,000 Chinese workers in Algeria, is clearly to use their own workforce. But the long-term success of Algeria-China strategic partnership is linked to a more balanced contribution in new projects such as the US$3.3bn Cherchell port for mega-container ships near Algiers. The lesson is valid for Sub-Saharan Africa where local employment and the development of local companies are major concerns for the population and governments.

The third challenge is about sustainable development and the ecological impact of large infrastructure projects. Norway and China have restored in April 2017 full diplomatic relations and resumed free trade negotiations, which opens the way in particular to cooperation in the area of energy between the two countries. But Norwegian companies, and Nordic firms in general, will venture into new projects with Chinese partner firms in Northern Europe, in the Arctic, or in third countries only if the activity has a positive impact on the environment, and especially the marine environment. This creates the opportunity for Chinese companies to operate internationally at the most advanced international standards of sustainable development and to focus on co-innovation with their foreign partners. Chinese contribution to the development of the infrastructure in Africa – railways, highways, ports, airports, pipelines, telecom – is a blessing for Africa’s economic development. But Chinese Belt and Road initiative in Africa will be also clearly assessed in terms of impact on the natural environment and society at large.

Finally, China’s Belt and Road initiative which contributes to the development of international trade should also be exemplary from the standpoint of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental.

Read more

Larçon, J.-P. (Ed.) (2017) China meets Europe in the Baltics. Singapore: World Scientific.