As the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies shot up in 2017, the myths and rumors surrounding blockchain have again triggered a number of mixed responses, ranging from the firm faith in anarchism founded by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009, to the heroic sentiment to change the world with technology, or to the greedy desire inspired by stories of people accumulating vast riches overnight through bitcoin. The only way out of the conundrum is to review the essence of blockchain, to understand the foundation underlying the disruptions that it is causing as well as the accompanying challenges—for they are the two sides of blockchain, the sources of optimism and criticism respectively. The aim of this article is to analyze both sides and provide a new perspective for a world in the midst of a blockchain fervor.

Read this article in Chinese

As the price of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies shot up in 2017, the myths and rumors surrounding blockchain have again triggered a number of mixed responses, ranging from the firm faith in anarchism founded by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009, to the heroic sentiment to change the world with technology, or to the greedy desire inspired by stories of people accumulating vast riches overnight through bitcoin. Whatever it is, the undeniable truth is that so many expectations have been placed on blockchain that it has become the default answer to be everything and anything. Not everyone is caught up in fantasy, of course, but we must be constantly mindful that not all of the high hopes we have for blockchain will become reality. This puts all conscientious blockchain supporters in a conundrum—they earnestly believe blockchain has the potential to create a revolution, but at the same time confront with seemingly irrefutable arguments from detractors.

The only way out of the conundrum is to review the essence of blockchain, to understand the foundation underlying the disruptions that it is causing as well as the accompanying challenges—for they are the two sides of blockchain, the sources of optimism and criticism respectively. The aim of this article is to analyze both sides and provide a new perspective for a world in the midst of a blockchain fervor.

The global blockchain enthusiasm started with the birth of bitcoin and the associated iconic and highly appealing political concept of decentralization. The idea behind bitcoin and its source code were first made public by the creator,Satoshi Nakamoto1, in a 2009 paper posted in the Cypherpunks developer community, who later become the first miner2to produce Bitcoins. Although Nakamoto disappeared from public view four years after the origin of bitcoin, his (or their) online postings and comments can still be found.

Actually, Satoshi inherited the predominant political beliefs held by the Cypherpunk community, which originated as an online forum founded in San Francisco in the 1990s. A large portion of its members support the founding of a society based on anonymity and free from government control. Members believe that in the digital age, privacy is the most fundamental citizen right. The only way to restructure our current society and allow every individual to achieve their own potential and true freedom is to create a new open society based on the principle of privacy protection. At the heart of this utopia lies cryptocurrencies. The bedrock of our modern currency system is the central bank, which acts as the lender of last resort and, along with the entire banking system of the society, keeps track of all currency transactions as an intermediary. Cryptocurrencies represent a breakaway from this traditional model and pave the way towards a new, decentralized world of anonymity. Bitcoin as a cryptocurrency appears to be perfect for this utopian world. Blocks of transactions linked together form the structure of the currency’s database. Its consensus mechanism, which relies on computing power rather than faith in a third-party institution, offers a good safeguard against double-spending3. Supported by a growing belief in individual freedom, Bitcoin’s functions may one day replace those of central banks and banking systems, and render them irrelevant.

But the birth of bitcoin is only the very beginning. The development and evolution of blockchain has split into two different paths since its inception. On one hand, developers in the open-source community continue to push the boundaries of bitcoin technology, hoping to create a set of generic technological standards that would allow it to be used in scenarios other than simply monetary transaction. A prominent example is Ethereum4, a platform for developing all kinds of blockchain applications. Based on the platform, smart contracts and DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) became the new focus and were believed to have the potential to change the current organizing mode and social structure. On the other hand, inspired by the possibility that bitcoin was able to replace third-party transaction intermediaries, players in the relevant sectors have become more inclined to regard Blockchain as a positive technological advancement, while revising or even distancing themselves from the beliefs of the Cypherpunk community. The banking system, as part of the centralized establishment revolutionized by blockchain, recognized the technology’s potential in lowering transaction costs and has become one of the earliest supporters of blockchain. Other market players consider blockchain as a useful tool to circumvent conventional regulatory systems and centralized finance regulatory authorities, selling tokens of their own creation which triggered a worldwide wave of ICOs.5

While the birth and rise of Ethereum is just what blockchain supporters hope to see, the revision of Cypherpunk ideals has caused controversy. In particular, the myriad ICOs, some of which were absolutely fraudulent, has led some to label blockchain as “a Ponzi scheme”. Therefore, the question comes that whether it is possible to embrace the positive while rejecting the negative, meaning to support the development of blockchain while hold the risks in check. More specifically, is it possible to allow the use of blockchain in various fields to release its potential while banning illegal ICOs? This is in fact the key question underlying blockchain governance. To answer it, we must first analyze and understand what a “token” is and why we need it.

As mentioned before, the success of bitcoin as a cryptocurrency can be attributed to not only its blockchain data structure (supported by hashing and timestamping) but also its innovative consensus mechanism, which relies on aggregate computing power. It is this consensus mechanism that makes reliance on a third-party transaction intermediary unnecessary and allows for a consensus in record keeping between different nodes in the network.

The aim of bitcoin’s mechanism design is to reward certain types of spontaneous behavior undertaken by participants while restricting other undesired behaviors to achieve collective, concerted action. As Michel Foucault pointed out, technology isn’t just a tool or a means to an end; it is, instead, a political actor whose means and ends cannot be separated. Just like Heidegger, Foucault makes the distinction between technology as a “thing” and technology as a “set of techniques”. Technology as a “thing” is a tool, an instrument, whereas technology as a “set of techniques” has the power to change attitudes, behaviors, and social relations. Blockchain, as a disruptive new technology, has just such power.

Take the bitcoin network as an example. Miners are the underpinning components of the network, but why would miners want to spare processing power to partake in the network’s computational activities? Bitcoin offers two types of incentives: a miner that successfully solves the puzzle to create a new block receives bitcoins as a direct reward; in addition, all transactions recorded into this block incur a transaction fee, which is passed on to the miner. It is for this reason that as the value of bitcoin rises, miners will continue to contribute processing power to the network, as long as the rewards they receive outweigh their costs. On the other hand, miners face certain restrictions as well, more specifically, restrictions on speculative activity. As previously described, the consensus mechanism of bitcoin relies on the “the rule of the longest chain”, associated with the aggregation of computing power. This is to say that to alter the ledger at will, one must control over 51% of all processing power contributed by the miners. But it has to be noted that there is no third party verifying bitcoin’s ledgers. The only way for people to attribute value to bitcoin willingly, is for them to trust all payees equally without any discriminations. Since the anonymity granted by bitcoin as a cryptocurrency means that since there is no way to pinpoint an account suspected of having altered its transaction details (or, in other words, created fake bitcoins), malicious tampering will cause all transactions suspectable and eventually bitcoin itself to be rejected because of loss of faith. Such an outcome would, of course, be disastrous for all miners, who count on bitcoin maintaining its value. Therefore, this constitutes a restriction: no one has the motive to control over 51% of all computational power to tamper the ledgers for their own ends.

In fact, this kind of reward-restraint mechanism is needed not just in the bitcoin network, but in all blockchain applications. Such mechanisms are often incorporated into the design of tokens. In an ICO, tokens are incentives as well as proofs for investment. In smart contracts, tokens can be used to ensure the parties regulate their behavior in compliance with the terms of the agreement. In many other blockchain applications, tokens are used as either a medium of exchange or proof of property ownership. This is why blockchain applications are inseparable from token design and use, and this is also where the difficulties of regulations lie: to support the growth of blockchain, the use of tokens has to be permitted, but it is always possible for tokens to be used for rogue fundraising and even fraud.

But in fact, all of these questions are about defining the aim of creating tokens, the attributes of tokens, and the source of tokens’ value. In order for tokens to incentivize and restrain certain behaviors, it must first have an appropriate source of value. If we can assess the different sources of token value and make informed selections, then it would be possible to overcome the difficulties in supervision.

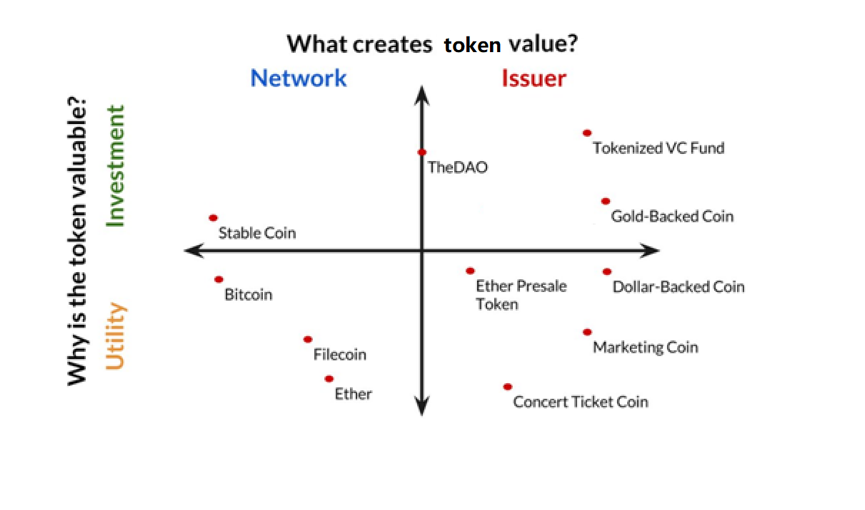

Peter Van Valkenburgh, director of research at Coin Center identifies the sources of token value by looking at two questions: “Who creates token value?” and “Why is the token valuable?” Token value can be created either by its issuers or the network. A token is valuable either because it could be used for investment, or because it could be used as a medium of exchange (i.e. possesses intrinsic utility) (see Fig. 1). Bitcoin, as a token, is generated online through a set of defined algorithms (therefore its value is created by the network) and is predominantly used as a medium of exchange6. On the other hand, gold-backed coins are created by the issuer according to the issuer’s own demands. The value of such coins are linked to the value of gold, which is not a medium of exchange, and therefore is used more for investment than completing actual transactions

With Peter Van Valkenburgh’s model it is easy to determine the source of value for each type of token. As policymakers, we should encourage more token creation in the network/utility quadrant, and less in the issuer/investor quadrant, because it is often in the latter quadrant that we see rogue ICOs.

Going back to the question at the start of the article: how can conscientious blockchain supporters find a way out of their current conundrum? Based on our analysis here, the reason that there seems to be a conundrum at all, is because much of the current understanding of the complex ideas and mechanisms behind blockchain is incomplete and superficial. It is much easier to comprehend blockchain’s potential to cause disruptions and the difficultly in regulating blockchain (particularly in regard to rogue ICOs), once the ideas and mechanisms are fully grasped. Therefore, to unleash blockchain’s untapped potential, the best way forward is perhaps identifying the most appropriate regulation targets and supporting the use of the technology in a wider range of acceptable scenarios.

1″Satoshi Nakamoto” is a pseudonym. The identity of bitcoin’s creator (or creators—there are those who believe bitcoin was invented by a group of people as opposed to one individual) remains a mystery to this day.

2″Miners” are nodes in the bitcoin network that generate new bitcoin through participating in computational activity.

3Preventing double-spending and counterfeit transactions is a key issue in cryptocurrency design. It is akin to combating counterfeit money in the context of fiat currencies. An example: what reason does payee “Bob” have to believe that payer “Alice” isn’t using forged cryptocurrency? With paper money, the only notes that are legal are those distributed and verified by banks, which are also responsible for settling transactions between different individuals as an intermediary. But banks and other third-party transaction intermediaries have no role in the bitcoin network, which means finding a new way to prevent double-spending lies at the core of the network’s design and the trustworthiness of bitcoin’s transactions. If Alice could pay the same digital token (or even a nonexistent token) to both Bob and Carl, how can the latter two trust and accept Alice’s payment? Bitcoin’s highly innovative answer to this question is blockchain and a proof-of-work system.

4Some of Ethereum’s aims including expanding the functions of bitcoin, supporting sidechains between different blockchains to allow for more types of transactions, and supporting the development of EOS, a blockchain operating system.

5Obviously unacceptable applications of bitcoin and blockchain (such as black market transactions and criminal activities) are not part of the discussion here. The aim of this article is to discuss generally acceptable applications of blockchain technology (such as ICOs), as the disputes surrounding these applications form the basis of the current controversy surrounding blockchain.

6Although bitcoin can be used for a range of speculative activities, it is still inherently a medium of exchange and therefore falls in the “utility” rather than “investment” quadrants.

(Images from internet and copyrights belong to the original authors.)