Culture is the essential catalyst of intelligence and an AI without the capability to interact culturally would be nothing more than an academic curiosity. However, culture can not be hand coded into a machine; it must be the result of a learning process.

Read this article in Chinese

What is AI and what is not AI is, to some extent, a matter of definition. There is no denying that AlphaGo, the Go-playing artificial intelligence designed by Google Deep Mind that recently beat world champion Lee Sedol, and similar deep learning approaches have managed to solve quite hard computational problems in recent years. But is it going to get us to full AI, in the sense of an artificial general intelligence, or AGI, machine? Not quite, and here is why.

One of the key issues when building an AGI is that it will have to make sense of the world for itself, to develop its own, internal meaning for everything it will encounter, hear, say, and do. Failing to do this, you end up with today’s AI programs where all the meaning is actually provided by the designer of the application: the AI basically doesn’t understand what is going on and has a narrow domain of expertise.

The problem of meaning is perhaps the most fundamental problem of AI and has still not been solved today. One of the first to express it was cognitive scientist Stevan Harnad, in his 1990 paper about “The Symbol Grounding Problem.” Even if you don’t believe we are explicitly manipulating symbols, which is indeed questionable, the problem remains: the grounding of whatever representation exists inside the system into the real world outside.

To be more specific, the problem of meaning leads us to four sub-problems:

1.How do you structure the information the agent (human or AI) is receiving from the world?

2.How do you link this structured information to the world, or, taking the above definition, how do you build “meaning” for the agent?

3.How do you synchronize this meaning with other agents? (Otherwise, there is no communication possible and you get an incomprehensible, isolated form of intelligence.)

4.Why does the agent do something at all rather than nothing? How to set all this into motion?

The first problem, about structuring information, is very well addressed by deep learning and similar unsupervised learning algorithms, used for example in the AlphaGo program. We have made tremendous progress in this area, in part because of the recent gain in computing power and the use of GPUs that are especially good at parallelizing information processing. What these algorithms do is take a signal that is extremely redundant and expressed in a high dimensional space, and reduce it to a low dimensionality signal, minimizing the loss of information in the process. In other words, it “captures” what is important in the signal, from an information processing point of view.

The second problem, about linking information to the real world, or creating “meaning,” is fundamentally tied to robotics. Because you need a body to interact with the world, and you need to interact with the world to build this link. That’s why I often say that there is no AI without robotics (although there can be pretty good robotics without AI, but that’s another story). This realization is often called the “embodiment problem” and most researchers in AI now agree that intelligence and embodiment are tightly coupled issues. Every different body has a different form of intelligence, and you see that pretty clearly in the animal kingdom.

It starts with simple things like making sense of your own body parts, and how you can control them to produce desired effects in the observed world around you, how you build your own notion of space, distance, color, etc. This has been studied extensively by researchers like J. Kevin O’Regan and his “sensorimotor theory.” It is just a first step however, because then you have to build up more and more abstract concepts, on top of those grounded sensorimotor structures. We are not quite there yet, but that’s the current state of research on that matter.

The third problem is fundamentally the question of the origin of culture. Some animals show some simple form of culture, even transgenerational acquired competencies, but it is very limited and only humans have reached the threshold of exponentially growing acquisition of knowledge that we call culture. Culture is the essential catalyst of intelligence and an AI without the capability to interact culturally would be nothing more than an academic curiosity.

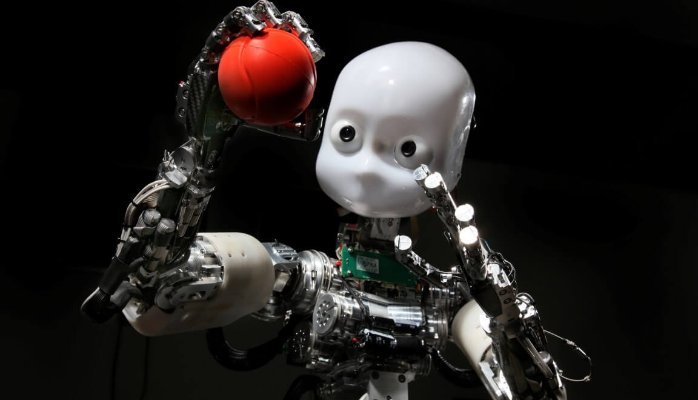

However, culture can not be hand coded into a machine; it must be the result of a learning process. The best way to start looking to try to understand this process is in developmental psychology, with the work of Jean Piaget and Michael Tomasello, studying how children acquire cultural competencies. This approach gave birth to a new discipline in robotics called “developmental robotics,” which is taking the child as a model (as illustrated by the iCub robot, pictured above).

It is also closely linked to the study of language learning, which is one of the topics that I mostly focused on as a researcher myself. The work of people like Luc Steels and many others have shown that we can see language acquisition as an evolutionary process: the agent creates new meanings by interacting with the world, use them to communicate with other agents, and select the most successful structures that help to communicate (that is, to achieve joint intentions, mostly). After hundreds of trial and error steps, just like with biological evolution, the system evolves the best meaning and their syntactic/grammatical translation.

This process has been tested experimentally and shows striking resemblance with how natural languages evolve and grow. Interestingly, it accounts for instantaneous learning, when a concept is acquired in one shot, something that heavily statistical models like deep learning are not capable to explain. Several research labs are now trying to go further into acquiring grammar, gestures, and more complex cultural conventions using this approach, in particular the AI Lab that I founded at Aldebaran, the French robotics company—now part of the SoftBank Group—that created the robots Nao,Romeo, and Pepper .

Finally, the fourth problem deals with what is called “intrinsic motivation.” Why does the agent do anything at all, rather than nothing. Survival requirements are not enough to explain human behavior. Even perfectly fed and secure, humans don’t just sit idle until hunger comes back. There is more: they explore, they try, and all of that seems to be driven by some kind of intrinsic curiosity. Researchers like Pierre-Yves Oudeyer have shown that simple mathematical formulations of curiosity, as an expression of the tendency of the agent to maximize its rate of learning, are enough to account for incredibly complex and surprising behaviors (see, for example, the Playground experiment done at Sony CSL).

It seems that something similar is needed inside the system to drive its desire to go through the previous three steps: structure the information of the world, connect it to its body and create meaning, and then select the most “communicationally efficient” one to create a joint culture that enables cooperation. This is, in my view, the program of AGI.

Again, the rapid advances of deep learning and the recent success of this kind of AI at games like Go are very good news because they could lead to lots of really useful applications in medical research, industry, environmental preservation, and many other areas. But this is only one part of the problem, as I’ve tried to show here. I don’t believe deep learning is the silver bullet that will get us to true AI, in the sense of a machine that is able to learn to live in the world, interact naturally with us, understand deeply the complexity of our emotions and cultural biases, and ultimately help us to make a better world. (This article originally appeared in LinkedIn, and is republished with authorization from the author)