China used to be a superpower in sugar production, with sugar being a bulk export commodity along with silk and tea.Until the late 17th century, sugar production technology in China was on the same page as the West. But why did the “Sweet Capitalism” revolution not happen in China? Why was China stuck with the “Joseph Needham Problem”—the inability to generate modern technologies—after a long period of technological advancement?

Read this article in Chinese

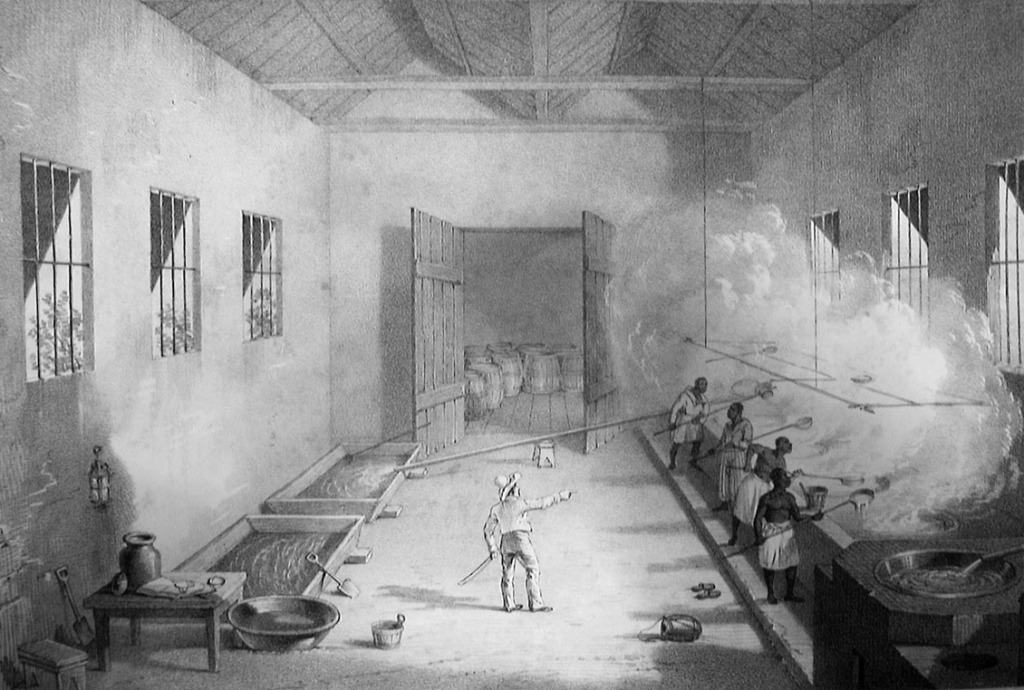

A print of a sugar boiling house in Europe of 19th Century by R.Bridgens. (the British Library )

When speaking of sugar, the things that tend to spring to mind are the Caribbean plantations, African slaves, the Atlantic triangular trade, etc. It seems to many researchers that sugar triggered all sorts of farming specializations and economic divisions, and thus, forged so-called “Sweet Capitalism.”

China used to be a superpower in sugar production, with sugar being a bulk export commodity along with silk and tea.Until the late 17th century, sugar production technology in Chinawas on the same pageasthe West. Nevertheless, when demand for sugar on the global market sharply increased by the end of 19th century, Southern China fell out of the competition as a traditional sugar production region. Since then, China has been a sugar importer.

Why did the “Sweet Capitalism” revolution not happen in China? Why was China stuck with the “Joseph Needham Problem”—the inability to generate modern technologies—after a long period of technological advancement? Are there possibly new explanations, aside from the high-level equilibrium trap of Mark Elvin and the involution development of Philip C. C. Huang? China: Sugar and Society – Farmers, Technology and World Market (hereinafter referred to as Sugar and Society) appears as an effort by author Sucheta Mazumdarto answer the above questions by focusing on particularly on sugar.

Insufficient domestic demand is believed to be the main reason for which the specialization of labor did not arise, and the technological advancement and industrial revolution did not arrive in the manufacturing sector of China. This is no more than a platitude, and Sugar and Society also shares considerable attention to demonstrate the lack of domestic demand in China. However, the impact that weak domestic demand could have on the industrialization and the technological advancement can be offset by external demand. The many successful examples of export-oriented economies provide ample demonstration.

Paradoxically, nevertheless, sufficient external demand may not necessarily provoke specialized production and technological advancement. The key lies in how the external demand can be satisfied.Looking at theBritish Industrial Revolution, Hobsbawmdiscovered a common feature in all fundamental inventions: the expansion of production by cutting costs and raising productivity.This applies to China as well.In the late 16th century and the early 17th century, China’s sugar industry experienceddevelopmentsin pressing and processing technologies, among which the most significant two werethe vertical double-roller sugar cane mill (which was inspired by the double-roller cotton gin, according to some people) and the technique of filtering sugar with clay. With such inventions,Mark Elvin’s explanation on technological stagnation is refuted. In fact, the latest data shows that the laborsaving technologies and equipment continued to be invented as far as the end of imperial China.

These technologies surely increased sugar productivity, and were nevertheless subject to a restriction with Chinese characteristics. This restriction relates merely to the size of the single production unit, rather than the input of labor force, as indicated by Philip C. C. Huang. In other words, any inventions for increasing productivity and saving laborare welcome within the scope of a single household, whereas inventions would be abandoned once they reachedbeyond this scope.

The multiple-roller sugar cane mill saved time with higher productivity, but required multiple workers in co-operationand additional labor for supervision, and thus, cooperation became necessary. In addition, it required the specialization of other sections as well, for example, the centralized drying chamber that emerged in Amsterdam in the same period. Such a mechanized and centralized mode of production, together with the extension of the production chain,undoubtedly appeared “over advanced” and could not easily accommodate to small farmer households and the individual labor mode. As for the economy based on rural household manufacturing, the simple equipment operated by one single family member proved to be an excellent choice.

Thus, the increasedproduction is based on the increased production units, and not acquired through an organizational model that centralizes production and adopts technologies that accelerate the increase in total production. By involving a large amount of small farmer households, agricultural China was surprisingly able to produce massive trading products, and could cater to the increasingly enlarged export demand in a relatively long period of time.

There is anobvious bottleneck in commoditization founded on the basis of scattered self-employed peasants;the small-sized farming and sideline production became more and more stretched in the face of the increasingly aggressive competition from overseas large-sized and centralized farming and manufacturing. The customs of theQing Dynasty led by Robert Hart analyzed reasons for the decline in Britain’s demand for Chinese tea in the 1880s and indicated that Chinese tea was“gathered from scattered bushes at corners and produced by millions of independent farmers, and then transported to a market which was disrupted by thousands of independent agents from different regions.”

The same situation arose in the sugar industry. Why did a “Sugar-Eats-People” movement not happen in China to enable the consolidation of land and the expansion of planting areas, and further transform landless peasants into workers on large-sized production sites? It was greatly caused by the control of the Qing Dynasty over powerful landlords and its support to small self-employed farmers since the rulers of the Qing Dynasty believed that, due to the land consolidation by powerful landlords,the resulting refugees became the main cause for the collapse of the Ming Dynasty. The multiple-son inheritance system was also unfavorable to the centralization of land, and in correspondence with the Permanent Tenancy System, the separation of “Surface Right of Land” with “Foundational Right of Land” made the centralization of land ownership meaningless: the “Foundational Right of Land” could be freely centralized, whereas the tenant farmers possessing the “Surface Right of Land” must be consulted, so as to determine if the land could be entirely used for planting the sugar cane or not.

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham ( 1900-1995 ), British scientist, historian and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science.

It would therefore be more favorable for landlords to rely on tenant farmers for the choice of crops and then to watch for opportunities for increasing land rent, rather than to take the initiative to alter the type of crops. By the middle of the 18th century, China’s population soared to 300 million, which intensified the competition for land, which allowed the landlords to increase rent and require a deposit and upfront payment.

As for many landlords, this revenue model of “waiting to collect rent” appeared more securecompared to becoming direct producers. Moreover, by operating the land themselves, their potential revenue could possibly decreasedue to the remuneration paid to employees, together with meal subsidies, tobacco subsidies and haircutting subsidies.Thus, even in newly developed “border” areas, such as Taiwan, those merchant-landlords chose to seek profits by dividing the land into small pieces and leasing the land pieces to tenant farmers and not to develop the large-sized plantations, even though theypossessed abundant capital and developed tens of thousands of acres of land with massive irrigation systems.

Besides, throughout the Qing Dynasty, the conflicts between village and lineage over control of critical economic resources such as land, water and markets had been widespread. In Southern China, such conflicts were further intensified due to hostility between Hakkanese and indigenous people. It is therefore required for the people to leave aside for the time being the divergence of interests between classes, and to collectively cope with the invasion of outsiders. The landlords would certainly strive to protect the “love” and ownershipof small farmers over the land, since villagers were needed as the main force in the group fight with weapons. The hardened structure of interest groups in village communities signifies the exclusion of outsiders and outside capital from purchasing and owning the land in village communities.

The following question is why those merchant-employers were also absent in the feast of China’s capitalism, whereas they had played a significant role in the capitalist process of European economies.If not becoming the large-sized direct producers (planter) of the means of production (sugarcane), still they couldscale up the manufacturing (the rolling of sugarcane and the sugar refinery) and become the leading entrepreneurs, and therefore transform themselves from the “capitalist on other’s territory” into the “capitalist on own territory”?Similar to the landlords who found that leasing land was more profitable than getting directly involved in planting, the merchants also found that profits were more secured at each link of circulation rather than getting directly involved in production. There was a price differential between sugarcane purchase and sales, the commission of sales, the interest incurred from loans to sugarcane planting and processing, the sales of fertilizer at prices above the market level, incomes from other materials and even from the instruments of production. Over time, the merchants became less and less motivated to acquire profits through innovation of technologies and expansion of production, and naturally, they were less inclined to invest in the abovementioned areas.

Small-scale planting is unfavorable to centralized production and manufacturing; the landlords and merchants tended to maintain the small-producer model, whereas they were capable of scaling up the planting and production. Through the synergy of all parties, a bizarre trend of commoditization but not specialization emerged in the agricultural sector of China. The farmers depended on the market for cash in order to pay the land rent and the interestowed to the merchants, but their relevanceto the market was half-hearted since they were unable to wholly rely on the market. The rural families must secure their survival needs first before participating in the market.

In fact, rice and other basic crops had been constantly cultivated in those cash crops areas,which aremost actively involved in the global market. When tea prices largely went downwards in phases, the tea growers destroyed the tea fields without hesitation, and turned to plant rice. As concluded by the customs of the Qing Dynasty, “it must be remembered that the Chinese tea, regardless of past or present, has been a kind of agricultural byproduct.”

The same scenarios happened to the sugarcane fields. In the first decade of the 20th century, with many new sugar producers joining the global market, such asthe Philippines, Java and the Japanese occupied Taiwan, and with many new sugar sources arising, such as the beet sugar of Germany, Austria-Hungary and California, Chinese merchants quickly found that the price of imported sugar was lower than the domestically produced sugar. Unlike the producers in Taiwan or Java who were connected to the market through a single crop, the small self-employed farmers in Southern China turned unhesitatingly to plant rice, vegetable, fruits and oil crops, when they found that the sugar price fell below the bottom line they set.

Unfortunately, when the global market took a favorable turn, the farmers and merchants who chose earlier to exit were already unable to reenter and participate in a new round of competition. (Translated by Gong Jia)